I release my novels here, on Substack, first. These are very early drafts, and released as I’m writing them. Plot holes happen, things will change a lot before release. If you’re liking it, let me know! If you don’t like something I did, consider this a great place to let me know that too. And subscribe to keep them coming!

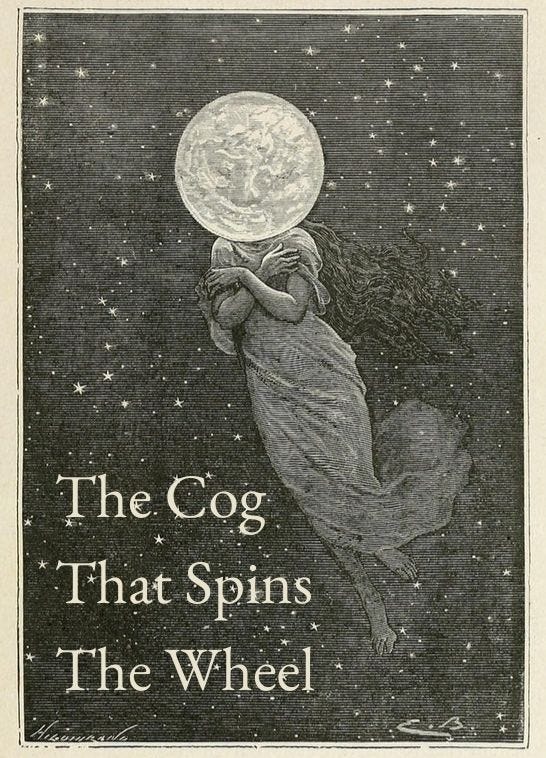

Chapter 1 - The Shape of the Moon

The biggest problem with life on the moon isn’t the lack of oxygen. It’s not the lack of an atmosphere, or the cold, or the unlivable nature of the whole place. It’s not even the gravity that sits at a sixth that of Earth’s, although it is sort of caused by that. No, if there’s one problem with that damn moon it’s something infuriatingly small. Something so tiny that off-planet you’d laugh about it with your friends over a couple of cold ones. But in the pit of your stomach, you’d feel a clench at the memory of it, the insidiousness of it, the everywhereness of it.

The biggest problem with life on the moon is the fucking dust. Tiny particulate matter, ground down from centuries of boots, tires, and meteor impacts, hangs in the air, carried on the currents of movement, to cover your clothes, your dishes, your eyes, your lungs. To be absorbed slowly, menacingly, into your blood until you’re no different than the moon you stand on. And then, finally, the moon eats you.

You don’t wear a respirator here, even inside the artificial life zones, those giant bubbles of increased gravity and oxygen where the air scrubbers whine constantly, and you’ll be dead in a couple of years. That’s just the way it is. So laugh about it over your beers, pretend you’re not scared of it. The dust will still be there to greet you next time you’re in town. It’s as unavoidable and inescapable as the death it carries.

When I dream about the moon now, I dream in monochrome. The two week solar cycle that leads to either everything washed white and burning in the sun’s luminous gaze, or in the night, haphazardly defined by the artificial lighting of shoddy street lamps. There’s only two colors there–light, and dark. And no matter how bright it is, the same black dust. Drifting in the air, accumulating on every surface, outlining the edges of your respirator, your goggles, your ears as you travel in between clean rooms.

Dust is your grave chasing you, better not let it hang around or it’ll bury you. That’s the saying up there.

You can always tell someone’s a mooner by how they sit down. It’s a gesture that defines the population, habitual and practiced, of tilting a chair and tapping it against the ground to shake the dust free before they sit. It’s a holy thing, they’ll do it even if they just saw a bot wipe everything clean. They’ll do it just to be damn sure there’s none of it collecting on them. You’ll see the baddest, meanest looking motherfuckers do it like they’re playing a game of musical chairs. Even they’re scared of it.

That was one of the hardest things to unlearn, the fucking chair tapping. Even now when I walk up to a table, my hands itch for it, my body longs to feel that slight vibration of the chair knocking against the ground. But you do that off planet and people will smirk to themselves, pitying you or judging you or who knows. That kind of half smile that makes you want to reach across the table, and smack it off their clean, beautiful faces. I refuse to give them that pleasure. People know I’m a mooner, I’d be hard pressed to truly cover that up with my entire life history being public knowledge, but fuck them, I’ll be damned if I give them something to laugh about. A chip on my shoulder? No, I have a fucking whole moon there, weighing me down.

Normally, the circuit stuck to the less depressing places–the red hills of Mars in their devastating contrast, the endless ice planes of Uranus where distant domed habitats are visible for miles, the lush greenery and brown dirt of earth. They skip the moon because poverty doesn’t televise well, and it’s all about those ratings baby. They skip the moon because accidentally capturing a dust child, heaving air in because their family can only afford defunct respirators and their lungs are already clogged at five years old, doesn’t make viewers feel good about watching a sport that burns money to stay warm. Do I hate them for that? No, they’re just running a business.

Okay, maybe I do a little bit.

So when the circuit went back, finally, to the ground that made me, I knew I had to win. I had to win it for the kids that wouldn’t live past five, but saw me and imagined something better. I had to win for that teenage girl that won a televised race here, and knew it was going to change her life. I had to win it for my dad, probably long since eaten by the dust, who taught that girl everything she knew. I had to win it for my mom, and all the other people the moon drug to an early grave, because if I didn’t, no one else would give a damn. If I didn’t, the circuit would slide off the moon like the traveling circus it was, leaving small handfuls of cash behind in some officials pockets, and nothing would ever change.

I wanted it more than that teenage girl wanted that first win. Maybe. But definitely for different reasons. Not that winning it was in much question at this point. Races had been getting tighter over the last few years, sure, and entire broadcasts were dedicated to wondering when I’d finally retire, which I usually turned off after directing two firm middle fingers at the screen when they mentioned my advanced age, but I wasn’t dead yet. I’d ruled this circuit since I joined it, twenty years ago, and that might not mean I won every race, but I had won a whole lot of them. Enough to make new racers stand straighter when I walked into a room, or stop me in the halls of our base camp asking for an autograph. Enough that when I announced a race was my focus for the season, which was probably my first mistake, the singular moment that cascaded all the events afterward, it made the rest of them nervous.

I didn’t see the tide was shifting. I was an idiot standing on the prow of her ship, staring at the sunset, not realizing that I was beached, and that when the sun did go down, I’d be alone in that darkness. Broken, crying, and choking on dust. But that’s leaping ahead, and if my dad taught me one thing when I’m telling a story, it’s to slow down and tell it in order. That’s the only time he ever told me to slow down, actually.

The problem is, I never know where to start. Was it when as a puny teen, I won my first race against the heavy hitters? Something fated from that day forward? Or was it in the instant before it all happened, before the chaos and the violence, some final mistake that I can’t even remember now? Maybe it was just that fucking moon coming back to claim me, to bury me in its dust.

Give me a race gate, a starting line, a line in the sand, or even just a hot little number waving a flag, and I’ll show you how to start though. Full fucking gas, leaning over the front wheel, searching for traction and keeping it pinned. Dumping my anger and fear, my hopes and dreams, my sadness and joy down through dual hemispherical tire treads into the soil. That same soil that birthed me.

Which is probably the best place to start.

I went to the moon to remind people I wasn’t done yet. I went there to reclaim my heritage, to show them what a mooner could do. I went to the moon to win.

Cover image taken from Émile-Antoine Bayard’s Illustrations for Around the Moon by Jules Verne (1870) (Public Domain)

That regolith is nasty. Microscopic obsidian razor blades. Still a showstopper for lunar base plans!

Intriguing opener and love the solar system-weary narrators voice. Most fascinated to see how the racing works across all the different planets and moons.